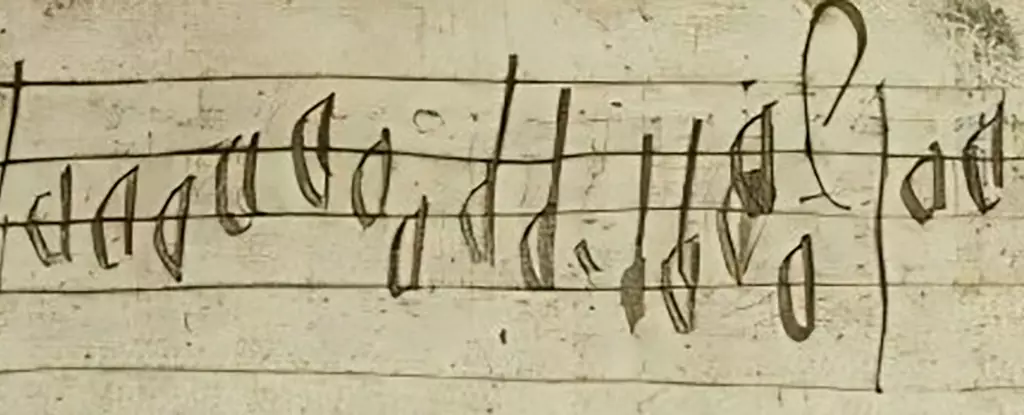

Music bears a unique ability to unite people through time and space, drawing connections between the present and bygone eras. Recently, researchers have made an enthralling discovery—an approximately 55-note piece of sheet music originating from 16th-century Scotland. This exploration not only illuminates a segment of Scotland’s musical heritage but also sheds light on the broader tapestry of pre-Reformation liturgical culture. The musical notation was unearthed in the margins of a highly significant book—the Aberdeen Breviary of 1510. Though its contemporary relevance may not be prominent, the Aberdeen Breviary represents Scotland’s inaugural full-length printed book, making this fragment an undoubted historical treasure.

The research was spearheaded by a collaboration between KU Leuven in Belgium and the University of Edinburgh in the UK. This teamwork has crucially modernized our understanding of Scotland’s musical traditions, offering a glimpse into a culture from which little else has endured. The resurgence of this musical note, previously lying dormant for centuries, reveals how music can keep its spirit alive through centuries of silence.

The musical notation, according to the researchers, is reminiscent of a Christian chant known as “Cultor Dei, memento,” which is still used in certain Anglican services during the Lenten season. Though the precise intention behind the notes remains a subject of debate—whether they were intended for instrumental guidance or choral arrangements—the mere existence of such notation allows historians and musicologists to piece together elements of sacred music that have otherwise vanished from historical records.

The fragment embodies a polyphonic structure, characterized by simultaneous melodies that interweave to form a harmonious whole—a testament to the intricate musical craft of its time. Musicologist David Coney from the University of Edinburgh articulated the emotional weight of this discovery, stating that it exemplifies a hymn that had been silent for almost five centuries. This revelation not only enriches our understanding of sacred music but also paves the way for the reconstruction of other parts that were historically obscured.

Historically, pre-Reformation Scotland has often been perceived as lacking a robust musical tradition, particularly in the realm of sacred music. However, scholars such as musicologist James Cook have begun to contest this narrative, suggesting that the passing years have unfairly obscured the richness of Scotland’s musical legacy. The musical discoveries, including this 55-note snippet, challenge the long-held belief that the Reformation obliterated quality music from Scotland’s ecclesiastical landscape. As Cook aptly states, the data retrieved from this fragment reflects that Scotland had its own thriving religious musicality comparable to that of its European counterparts.

The intertwined relationships between various historical landmarks, such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St Mary’s Chapel in Rattray, are indicative of a widely engaged community in the creation and preservation of sacred music. The story behind the book which contained this music serves as a compelling reminder of the condition of cultural artifacts and the hidden gems within materials thought to be exhausted.

The implications of this musical fragment extend beyond its immediate context. The research team is now catalyzed to investigate further similar texts in Scottish libraries and archives, examining blank pages and margins where forgotten melodies may still lie. The study of historical texts can lead to the unearthing of more compositions that might accompany the already fragile remnants of music from the early 16th century.

Music not only chronicles the social and religious milieu of its time but also provides a unique lens of understanding through which we can evaluate the complexity of historical narratives. As scholars delve deeper into the inkwell of history, fresh rediscoveries promise to reshape our perceptions, offering precious insights into the rhythms that once infused life into ancient Scottish churches and cathedrals.

This exploration highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between musicology and history in fostering a nuanced understanding of cultural heritage. The 55-note fragment serves as a microcosm of the broader story of Scottish liturgical music, reminding us that while many sounds may have faded, the spirit and resonance of these musical echoes have not. Through continued investigation, we may uncover the rich tapestries of culture that contribute to the symphonic legacy of our past.

Leave a Reply